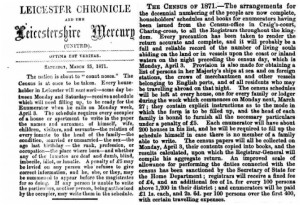

“Leicester had a child mortality rate which was twice the national average and on a par with London, Manchester and Liverpool”, explains Ned Hewitt in his excellent book ‘The Slums of Leicester’. Each summer, an annual epidemic of diarrhoea killed many of the elderly and very young. “By 1871 this yearly scourge was killing one in four Leicester children before their first birthday.”

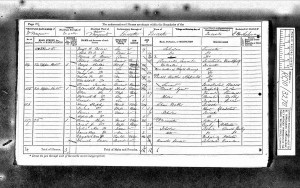

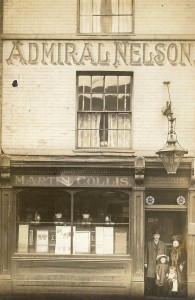

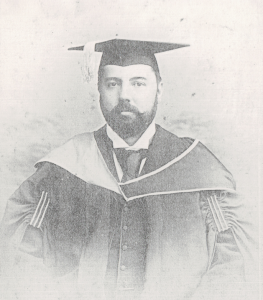

Statistics can often feel rather dry; put them in the context of a particular family, however, and they become more meaningful. George Jennings Collis was one of ten children, four of whom died in infancy. It’s a reality that’s unimaginable by today’s standards, but in 1870s Leicester it was the norm.

Ned Hewitt continues, “The cause of this annual [diarrhoea] epidemic was hotly debated. Summer heat, gas from the sewers and lack of ‘mothercraft’ on the part of women working in factories were all blamed. However, the real reason was the town’s inadequate sewers and the resultant insanitary conditions.”

To be exactly sure of the cause of the Collis boys’ deaths would require ordering four death certificates – an expensive business – and so at this stage I’m surmising that the lack of clean water and poor sanitation were contributory factors, if not directly the cause of their death; the Collis family home at the North Bridge Inn was sandwiched between the River Soar and the Leicester Canal, in the thick of it. What is clear is how precarious life was when George Jennings Collis was an infant in the 1870s. He was lucky to survive, with four brothers dying either side of him.