“Leicester had a child mortality rate which was twice the national average and on a par with London, Manchester and Liverpool”, explains Ned Hewitt in his excellent book ‘The Slums of Leicester’. Each summer, an annual epidemic of diarrhoea killed many of the elderly and very young. “By 1871 this yearly scourge was killing one in four Leicester children before their first birthday.”

Statistics can often feel rather dry; put them in the context of a particular family, however, and they become more meaningful. George Jennings Collis was one of ten children, four of whom died in infancy. It’s a reality that’s unimaginable by today’s standards, but in 1870s Leicester it was the norm.

Ned Hewitt continues, “The cause of this annual [diarrhoea] epidemic was hotly debated. Summer heat, gas from the sewers and lack of ‘mothercraft’ on the part of women working in factories were all blamed. However, the real reason was the town’s inadequate sewers and the resultant insanitary conditions.”

To be exactly sure of the cause of the Collis boys’ deaths would require ordering four death certificates – an expensive business – and so at this stage I’m surmising that the lack of clean water and poor sanitation were contributory factors, if not directly the cause of their death; the Collis family home at the North Bridge Inn was sandwiched between the River Soar and the Leicester Canal, in the thick of it. What is clear is how precarious life was when George Jennings Collis was an infant in the 1870s. He was lucky to survive, with four brothers dying either side of him.

Prof Jack Simmons picks up the story in ‘Leicester Past and Present: 1860-1974’:

“In the past the river had been the town’s greatest friend. Leicester owed its very origin to the Soar, as well as a handsome contribution to its economic growth. But the river had always been liable to serious flooding, which restricted the use of otherwise valuable land on its banks. And by the middle of the nineteenth century it had come to be, from one cause or another, a fertile source for disease.”

Works were undertaken to introduce a sewerage system in the 1850s, yet “In the course of the ‘sixties, as the system came to be more and more overloaded, its deficiencies grew horribly plain. During some of the hot summers of that decade, the stench arising from the Soar became unbearable, and the ‘summer diarrhoea’ that rendered the town notorious was generally attributed to that cause.” According to an article in Builder, in 1868 there were four times as many deaths from that malady in Leicester as in the whole of London.

Reservoirs were constructed in outlying villages of Thornton (1853), Cropston (1866) and later at Swithland (1894) to improve the supply of clean water. A sewage pumping and drying station was erected near the Abbey. And, as Colin Ellis writes in ‘History in Leicester’, “Floods were mastered, after much tinkering, by blowing up a number of obstructive mills and straightening the course of the river.”

This evocative photograph (Leics Records Office) is believed to show Frog Island in the 1870s – a short distance away from the Collis household – possibly depicting the construction of Evans Weir; the building of weirs did much to reduce flooding in the town.

“Meanwhile, the sewerage system remained unaltered, ” Jack Simmons continues, “Plan and counter-plan were put forward; inquiries were held, and every proposal was turned to ridicule by its rivals… by 1873 it was perceived that any effective solution to the problem must provide for three things in conjunction: for better sewers, for carrying away storm waters, and for greatly improving the river, so as to eliminate the flooding to which it was constantly subject.” It took many years for the solution to be implemented – the ‘Flood Prevention Scheme’ was effected between 1876 and 1891, and a fresh system of main sewers was finally begun in 1886. Too late to help four little Collis boys, and many other infants living in the streets and courts close by.

What can we learn from this episode? Infant deaths are easy to skip over – they can fall between census returns and often leave sparse documentation in their wake; yet take a little time to study them, with help from local history books and online resources, and you’ll develop a deeper understanding of your family’s living conditions.

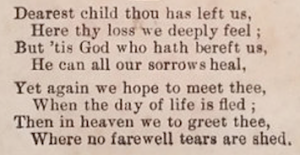

Thankfully, George Jennings Collis – and five of his siblings – survived to adulthood. But the memory of four lost children must have lingered, a shadow on their parents’ lives. Two of their baby sons – the first James Jennings and John Collis – had not survived long enough to be baptised, and were buried in public graves. The other two – Alfred Jennings and the second James Jennings – were laid to rest in the family grave. In their memory – and without wishing to sentimentalise it – we close with a verse taken from a child’s mourning card of the 1870s:

Sources:

The Slums of Leicester by Ned Hewitt

‘Leicester Past and Present: 1860-1974’ by Jack Simmons

One reply on “George Jennings Collis: foul floods and four lost brothers (1870s)”

[…] Foul floods and four lost brothers (1870s) […]