Fast forward a few years and it’s time for the 1881 census. The Collis family has moved from the North Bridge Inn to the Hinckley Road Brewery. It’s a fine-looking place, standing at the junction of Hinckley Road and Great Holme Street, a spectacle for those approaching town along the Narborough Road.

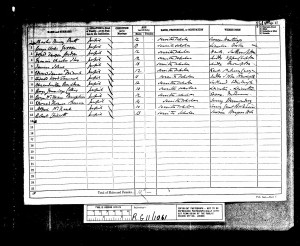

Almost everyone is there on the night of 3rd April 1881: father John George Collis, mother Emmeline and children Cary (16), Emmeline (12), Walter (5) and Amy (2). But George Jennings Collis is missing; he’s not tucked up in bed at home like his siblings or staying with relatives elsewhere in Leicester. He’s 150 miles away, trying to sleep in a dormitory at St Saviour’s School near Ardingly, Sussex.

Unique amongst his siblings and cousins, George appears to be the only Collis sent away to school. Maybe his parents had particular aspirations for him as the eldest son? His mother Emmeline had been a pupil teacher for several years before she married, so perhaps she’d spotted signs of early promise in his academic studies? There were many other independent schools closer to hand, so why choose St Saviour’s so far away?

St Saviour’s had been founded in 1858 by Canon Nathaniel Woodward, initially in Shoreham and then relocated to Ardingly – from which it later took it’s name of Ardingly College. Woodward was a pioneering Church of England priest who founded 11 schools aimed at educating the middle classes. He sought to provide education based on “sound principle and sound knowledge, firmly grounded in the Christian faith”.

It might have been this faithful focus that attracted George Jennings Collis’ parents to send him there – though there’s scant evidence that they were especially fervent in their Christianity. Take a closer look at the 1881 census: 10-year old George is listed as a ‘Servitor Scholar’. It’s time to get in touch with the Ardingly school archivist to find out more.

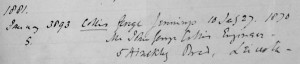

Archivist Andrea King is a great help. “Servitors paid a reduced fee and helped with various menial duties,” she explains “but they were able to attend some lessons.” She unearths a copy of George’s admission record:

Aged 10, he was admitted on 5th January 1881. His father John George is described as engineer – his day job, alongside running the Hinckley Road Brewery in the evenings. Despite having two jobs, maybe George’s father couldn’t afford the full fees for him to attend such a prestigious school, so joining as a servitor provided a much-needed subsidy? He was not alone: other Ardingly boys had fathers had worked as a carpenter in Leatherhead, a boot manufacturer in Hackney, a plumber in Bridport and a commercial traveller in Bristol.

Andrea continues “I think George must have transferred from being a Servitor as by July 1882 he is no longer shown in the Servitors’ Form class list but is in the Grammar School Upper Second form. He seems to have been very sporty, playing cricket and being goalkeeper in football.”

How could I get a sense of his school days? I head to the Society of Genealogists, which holds an extensive collection of school histories. Sure enough, there are several books relating to Ardingly.

‘The Ardingly I Remember’ (edited by Nigel Argent) sets the scene: “Nathanial Woodward’s work as a curate in Bethnal Green in the early forties of the last century [1840s] showed him how inadequate were the existing facilities for the education of the middle classes. Good State secondary schools were lacking and the fees of the old public schools were too high. Woodward’s ‘A Plea for the Middle Classes’, published soon after his move to Shoreham, announced his intention of building secondary boarding schools of several grades to meet different levels of income. Lancing and Hurstpierpoint soon followed, to cater for the sons of noblemen, gentlemen and clergymen on the one hand and for the sons of professional men and farmers on the other.”

Woodward’s high profile campaign garnered considerable publicity “in leading newspapers, hundreds of pulpits and at public meetings all over the country… Oxford and Cambridge Universities also set up high-powered committees to raise funds.” There were dissenting voices too – Woodward was accused of ‘Romanising tendencies’ and demanding compulsory confession. In fact, “the boys got a full Christian education according to the doctrine of the Church of England, the boys being taught the Catholic faith, without any extremist teaching.”

By the time George arrived the school buildings had been developed. As Rupert Perry writes in ‘Ardingly 1858-1946: A History of the School’: “Slowly, but surely, the buildings began to rise on the hillside in mid-Sussex. Ardingly enjoys the finest situation of all the Woodward schools; indeed it is doubtful that any English school has a better.” He continues, somewhat rapturously, “The wonderful view from the Terrace leaves a deep impression on the visitors… Below lies the lake, fringed with reeds and backed by the tall trees of Infirmary Woods, where the rooks build their nests… How charming are these woods in spring, when snowy masses of gean and wild cherry-blossom break into the delicate green fringe of every copse. How grand are these same woods when autumn tints clothe the whole valley in mellow dignity.”

By 1880 the North School had been opened and numbers rose to a high-water mark of 458, but the buildings were uncomfortably crowded and by 1890 the roll was reduced to only 350 boys. Coaching from Mr Hilton and Mr Cunnington ensured that the school produced some first-class cricketers and footballers.

For a sense of daily life for the boys, I turn to some old boys’ personal memoirs. CEC Kendle recalls his early days at the school in 1884:

“How I remember my first day as a Dormitory boy, aged 9 – unmercifully ragged by a Prefect and dragged around the various day rooms for inspection. Rampant bullying and staged bare-knuckle fights were daily occurrence in those days, for supervised leisure time activities were non-existent. Very few of the masters had ‘paper’ qualifications or made any great effort to teach. We did our Maths on slates. Even in the VIth Form, lessons were vague and allusive.

The most vivid memory I have of the reigning Head Master was his appearance in the pulpit with a highly illuminated card bearing the words “THOU GOD SEEST ME”. In this late Victorian era, Chapels were very long a numerous; twice a day and three times on Sunday.

There were two ruthless punishments in vogue: Soxing and Twigging. The former of which consisted of face slappings. Failing half marks during a period, very often a dozen boys would be subjected to strikes on their cheeks. Twigging ie birching was a serious affair, often inflicted for paltry offences.

The food was atrocious. We had meat twice a week only, bread and butter for breakfast, ditto for tea. It was a hard life. The water supply was in a dug out, the lighting shocking, the sanitation Siberian… The old Tuck Shop, about the size of a coffee stall, stood on the site of the present School Library. The popular choice was Sussex cakes, 2 at 1d.”

And so it is, on census night – Sunday 3rd April 1881 – that we find George asleep in a dormitory at Ardingly. He has attended chapel three times today. He’s been given the run-around all afternoon by some of the senior boys. He’s written a letter home to his family, 150 miles away. Weary from his exertions, he slumbers.

Sources:

Census returns from Ancestry

Andrea King, archivist at Ardingly College

Schools collection at the Society of Genealogists

One reply on “George Jennings Collis: servitors and soxing at Ardingly (1881)”

[…] Servitors and soxing at Ardingly (1881) […]