A sturdy black patternmaker’s tool chest sits in the corner of my living room. It’s probably the largest heirloom that has made its way to me. Day to day, it doesn’t get any use – I’m not too handy in woodworking – yet I still get great pleasure from being its custodian. The tool chest embodies much about my Collis ancestors, many of whom worked as engineers’ patternmakers. Open up the lid and stories begin to emerge.

The tool chest, or many of the tools at least, originally belonged to my great great grandfather, Martin Collis (1853-1912); most of the chisels and planes inside are stamped ‘M COLLIS’. But it was his son – Martin Shipley Collis (1882-1951) – who probably made most use of it, working in the pattern shop at engineers AA Jones & Shipman and later as a self-employed patternmaker in partnership as Shipley & Collis. More of which shortly.

As a child, I remember the tool chest sitting in our garage – under cover and apparently under-used, even though my own father was a carpenter and joiner. A carpenter has need of hammers, screwdrivers and saws to make staircases, kitchens and cabinets. But inside a patternmaker’s chest you’ll find a very large number of specialised tools, particularly chisels and planes needed to shape and hone wooden models (or patterns) ready for casting in a foundry. So most of the tools in the chest – such as the spoon chisels shown above – have probably not been used since the 1920s.

The first recorded patternmaker in my family was John Collis (c1770-1829), who worked at Cort’s foundry in Leicester from around 1803. After a respectable working life of twenty years there, he came a cropper – imprisoned for stealing tools – and, after early release, he ended his days working at Brettell & Barwell’s foundry in Northampton. You can read more about the trial of John Collis here. In turn, three of John’s sons and nine of his grandsons worked in foundries or the engineering industry: three as patternmakers (sometimes called model makers) and others variously described as engineers, smiths, mechanics, iron turners or iron moulders.

So, there was a rich history of foundry work in the Collis family, primarily in Leicester but with a London offshoot. The London branch included another John Collis, developer of the Collis pallet truck; but that, as they say, is another story.

Let’s return to take a closer look at Martin Collis, with whom the tool collection began. After serving his apprenticeship at William Richards’ foundry – an 1868 newspaper snippet helps me make the connection to Richards being his employer – he continued as a model maker for over twenty years (1871-1891 censuses), before switching careers to become a publican. Foundry patternmakers typically used their own tools in the foundry workshop – hence the importance of stamping your name on anything that might go astray, either by mistake or at the hand of a less scrupulous workmate.

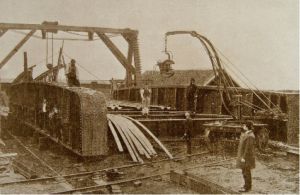

Wm Richards & Co was established in 1844, initially alongside Cort’s foundry near Belgrave Gate and relocating in 1874 to the Phoenix Foundry on Martin Street, which was served by its own railway sidings. The firm was loosely described as ‘constructional engineers and jobbing iron founders’ and some of the larger projects included making gasholders, iron-framed buildings and railway viaducts. When passing through Waterloo East railway station a while back, I spotted that several iron columns on the platform were badged with ‘W Richards, Leicester’. And (thanks to Tony Pugh in the Leics Industrial History Society journal, spring 2017) here’s a photo of a 60-ton girder bridge for Clapham (Bedford), being assembled in 1888 under the supervision (it is believed) of Henry WH Richards. Who knows, Martin Collis might have had a hand in helping design the components for this girder, though in fact it’s more likely that detailed patternmaking skills were more useful in designing stone-crushing equipment or engine turntables, in which the firm also specialised.

The family photo below (c1892) shows Martin Collis and his wife Elizabeth, with their children Ada Elizabeth, Martin Shipley and Leonard George. Around this time, Martin was making the shift from working as a patternmaker to becoming a publican – a career that he pursued for the next twenty years or so, owning six different pubs, until his early death in 1912. But a few years after this photo was taken, his eldest son, Martin Shipley Collis (known as ‘Matt’) followed in his footsteps by becoming a patternmaker.

I’d long known that Matt Collis, my great grandfather, worked as a patternmaker at the Leicester engineering firm of AA Jones & Shipman. And another treasured heirloom – his gold pocket watch – reveals the years he worked there, as it’s inscribed: “Presented to MS Collis, 1906-1919, Held in Highest Esteem by AA Jones & Shipman and Staff”. As he would have started his apprenticeship around the age of 14, in 1896 or thereabouts, it seems that he must have worked elsewhere initially – at Wm Richards’ Phoenix Foundry perhaps? – before joining Jones & Shipman in 1906, when it was still a fledgling firm.

As the company’s history (Tools that Built a Business: The Story of AA Jones & Shipman Ltd) explains, the firm was established in 1899 by two ambitious young men – Frederick Pollard and Frank Shipman – as makers of tools and accessories mainly for the nascent motor industry. Shipman was a talented patternmaker and draughtsman, with a wealthy father able to bankroll the business in the early days. And they were later joined by commercially savvy Alfred Arthur Jones: “Jones was no engineer, but he had what Shipman and Pollard lacked, a flair for market needs an exceptional ability to push the goods”. Company catalogues display their wares, which included drilling and milling machines, grinders, and cutters, along with associated tools and ‘specials’ such as equipment for sugar rolling mills.

Matt Collis initially worked at the pattern workshop in Humberstone Gate but within a few years the firm relocated to New Century Works on East Park Road. Despite the forward-looking name, it was still gas-lit until 1911 and poorly heated. “Working hours were long: from 6.30am to 6pm, with half an hour from 8.30 to 9 am for breakfast and another half-hour from 1 to 1.30pm for lunch. Saturday was a half-day. The ‘canteen’ was a row of gas jets under the eaves of the building where the men handed in their bacon and eggs to be cooked and their cans to be filled with tea. They ate their lunch at the bench or desk.” The enterprise grew and by the end of 1913 New Century Works comprised 37,400 square feet of space on three floors, employed 350 people and used 300 machine tools to produce about 3000 machines annually.

To my delight, the book includes a photo of the pattern shop in 1911, showing Matt Collis as foreman (in a white overcoat, on the right) and his colleagues all ankle-deep in wood shavings. Here we are in the thick of it. And it’s possible that Matt’s tool chest was sitting in one of the recesses, ready for him to work with the draughtsmen or his fellow patternmakers on shaping and honing the design of a new component. Perhaps later that day he reaches to use the odontograph to calculate and create a cogged wheel, or picks up one of the many small planes to refine a bevel, in the pursuit of pattern perfection.

As his pocket watch indicates, Matt Collis finished working at Jones & Shipman in 1919. Throughout WWI the firm had been busy in the war effort: “It had been an engineers’ war,” according to the company history, “fought as decisively at the bench as in the trenches, and the contribution of the machine tool industry had been vital, not only for the production of munitions, transport and fighting vehicles, ships and aircraft but also for agricultural and constructional equipment.” However, post-war, the industry slid into an economic crisis and Jones & Shipman had to lay off hundreds of employees, including Matt; by the early 1920s it had shrunk back to the size it had been 15 years earlier.

Rootling around the bottom of the tool chest, I find a length of hardwood, mahogany perhaps, with a hole in one end. Its purpose as a tool isn’t at all clear, but it has special interest as Matt Collis and a succession of his workmates have stamped their names into the wood. A parting gift when he left the firm maybe, as a memento of his life in the patternmakers’ workshop. Dovetailing these names with 1911 census research, I’m able to flesh out the team: Tommy Tuckley, Charlie Medlicott, Fred Harding, Bill Barton, D Sutton, JW Scotney, George Pegg, W Law, George Shipley, SR Hown and A Merrall.

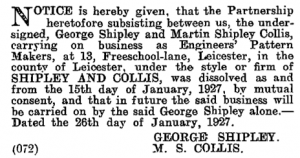

Among those names is George Shipley, who was Matt’s uncle. It appears George largely worked as an independent patternmaker; admittedly, he was ‘patternmaker, foundry’ in the 1891 census but he was later recorded as ‘own account’ at 34 Gladstone Street (1901), and ’employer’ at 13 Freeschool Lane (1911). So, when Matt left Jones & Shipman it was a natural progression to go into partnership with his uncle George. Thus, the black tool chest is moved into 13 Freeschool Lane and the partnership of Shipley & Collis is established. It was a partnership that ran for almost ten years, until they decided to part ways in January 1927, as set out in this London Gazette extract.

Matt Collis moves his tool chest back to his home at 2 Green Lane Road, and he starts a new career as a wireless dealer. Some of the tools might have been used from time to time – for undertaking house repairs or perhaps at the wireless shop – but largely it signals the end of the tool chest’s working life. And now, getting on for a century later, it sits in the corner of my living room, gathering dust but packed full – not only of tools, but also of stories and connections from my family history. A tangible link back to my patternmaking ancestors.

One reply on “Heirlooms: a patternmaker’s tool chest”

[…] with his uncle George Shipley on Freeschool Lane – and you can dip into his tool chest here: a patternmaker’s tool chest. He later set up as an electrical and wireless dealer with shops at 202 Melbourne Road and 2 Green […]