Graham Barker tracks down three Leicester landmarks constructed by his relative, Victorian building contractor Frederick Major

“He was a very active man, and always endeavoured as far as possible to walk wherever he wanted to go. In particular he objected to riding in tramcars. He also had an excellent memory, and could have written an extensive history of the city in the last century.” This extract from Frederick Major’s 1924 obituary captures something of his character – still sprightly and sparky, even at the age of 92 years old.

It’s disappointing that we will never read the history of Victorian Leicester that my relative Frederick Major could have written, woven with memories gathered over his long life working as a building contractor and town councillor. In the absence of his memoirs, how can I get a clearer picture of him? Do any of his buildings survive today, I wonder?

Read on, or download the full story here: Frederick Major, building contractor in Victorian Leicester

Before immersing myself in his building work, I remind myself of his family background. Born in 1831, Frederick was the eldest son of Thomas Major and Mary (nee Duxbury). His childhood was spent around Canning Street and Grafton Place, in the shadow of St Margaret’s Church and within a whiff of the gas works.

Frederick’s father appears streetwise and enterprising – being progressively described as a labourer, higgler, carman and timber merchant – but when young Frederick decided on a trade to follow, he was taken under the wing of his maternal uncle, bricklayer Thomas Duxbury, who was living with the Major family during Frederick’s formative years (1841). As a youth, Frederick no doubt helped with carting materials to site, hefting hods of bricks up to the scaffold platforms, and mixing mortar, before learning the craft of laying stretchers and headers in a variety of traditional bond patterns. Working alongside stonemasons, carpenters, roofers, plumbers and decorators – as well as the occasional architect – he gradually masters his trade.

Uncle Thomas Duxbury provided Frederick not only with employment as a bricklayer, but also with the introduction to his wife-to-be; Elizabeth Barker, who worked as a servant in the Duxbury household on Carrington Street (1851) becomes Frederick’s wife in 1855. The newly married couple settle first in Burley’s Lane and later in Mansfield Street – with Frederick’s parents virtually next door in both cases – and over the next twenty years, they have eight children together.

The British Newspaper Archive proves to be a gold mine, helping me piece together aspects of Frederick’s working life. By the 1860s he’s describing himself as a builder – an indication that he’s engaged with more substantial projects on his own account. There’s a short-lived partnership with James Fowkes, but the latter’s drunken escapades clash with Frederick’s temperance principles and the partnership is dissolved in 1865. Striking out alone, we find Frederick advertising for an apprentice (1871), “several skilled bricklayers; must be non-society men” (1875), “two good plasterers wanted, to take the labour of three houses” (1876), and seeking “a young man as Waggoner” (1883).

It proves tricky to identify houses that Frederick and his men built. Indeed, it’s often easier to see what they didn’t build, as he tenders unsuccessfully for a variety of council contracts, sometimes competing against as many as twenty other building firms. Frederick has sporadic success pitching for smaller-scale jobs, including workshops for the Institution for the Blind on the High Street (1873), “an additional staircase on the south side the Temperance Hall” for £385 (1882), “the pointing of the chimneys of the Workhouse” (1883), “a plant propagating house to be erected in the Abbey Park, for £183 5s” (1884), and a much more substantial contract for “the erection of the new Melbourne Road School” £12,733 (1890). Other newspaper reports indicate him building a house on Church Gate (1874), undertaking alteration works at Ellis & Whitmore’s worsted spinning factory near West Bridge (1876), and carrying out demolition works at the New Town Arms, Milton Street (1891). And, like many builders, Frederick also became a landlord, letting a storage site in Mansfield Street (1871), “the Forest Dairy, with shedding for 10 cows” (1879), and “two good family houses, also Cottage House” (1880).

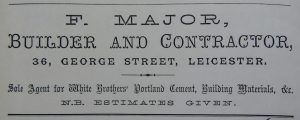

Frederick and his family lived alongside his builder’s yard and workshops – for around twenty years in Mansfield Street and, from 1878, at 36 St George Street: “a commodious Freehold 3-Storey Dwelling House with workshop, office, mason’s brick built and slated shed, and large yard… containing a total area of 586 square yards” which he bought at auction for £1729. His relocation notice announces him also as “Sole Agent for JB White’s Portland Cement,” suggesting some diversification as a builder’s merchant, perhaps to complement his parents’ timber yard at Mansfield Street.

Alas, within a year of moving to St George Street his beloved wife Elizabeth dies in 1879, leaving Frederick with a handful of children ranging from 3 to 20 years old. Eldest daughter Clara takes over running the household and raising the younger children, whilst sons Arthur and William begin working for their father as a bricklayer and clerk respectively.

Whilst the evidence of Frederick’s house building projects is somewhat piecemeal, my newspaper search reveals three of his larger projects that merit a closer look.

1874-5: Parsons & Brown warehouse and showroom, Market Place

Wandering through Leicester Market Place today, it’s easy to miss the surrounding architecture. This photo from the early 1900s gives a clearer view of the eastern parade. Standing to the left is one of Frederick Major’s buildings, the five-storey warehouse and showrooms of furnishing ironmongers, Parsons & Brown, towering in buff brick and stone mouldings, and straddling a pedestrian cut-through to Gallowtree Gate at the left-hand bay. Seven arched windows at the first floor level optimised the sunlight beaming into the “large show rooms for the display of register stoves, marble chimney pieces, fenders, fire-irons, kitchen ranges” as Parsons & Brown advertised at their re-opening in May 1875. Customers were also encouraged to visit their “large room for iron and brass bedsteads, lawn mowers… and patent mangling and wringing machines.”

The construction work was not without incident. In August 1874, two bricklayers and a carpenter’s apprentice employed by Frederick fell some 30 feet from a scaffolding board that gave way under their weight. Thankfully, none was badly injured, with William Millythorne, who had “been rendered quite helpless by injuries about the head”, later saying “his chief concern was about his plumb-rule, which had unfortunately been broken in the accident.”

1884-7: Co-operative Society shops, stores and offices, High Street

Some ten years later, Frederick Major is appointed main contractor for the construction of new shops, stores and offices for the Co-operative Society on the High Street. It’s a rather more elaborate structure than the Parsons & Brown warehouse; architect, Thomas Hind – whose design was featured in Building News (12 Dec 1884) – adopted a Queen Anne style, with red brickwork, terracotta carved panels and dressings of Ancaster stone.

Four shops were incorporated at street level, whilst the cellars – well lit from glass pavement lights and rear windows – were used as a workroom for the shoe-making department, and for storing drapery and grocery goods. The first floor was occupied as offices, a boardroom, carpet room, and dressmaking and tailoring workrooms. Above, on the second floor, there was a reading room and library, and a small assembly room for the society’s business meetings that could also be hired for musical and other entertainments.

The Co-operative chairman, Benjamin Hemmings, laid the memorial stone on 4 March 1884, and – by way of a time capsule – a bottle containing coins and documents relating to the Co-op’s history was bricked into a cavity. A “rearing supper” to celebrate the completion of the main structure was held in November 1884 at the Assembly Rooms when “upwards of 150 persons, who had chiefly been employed in the erection of the building partook of an excellent and substantial repast”. As well as Frederick, the assembled crowd including his nephew John W Barker, who undertook the painting work.

Within three years, owing to “the enormous growth in all directions of the operations of the society”, the premises needed to be extended along Union Street and Freeschool Lane. The same team came together again – Thomas Hind as architect and Frederick Major as main contractor – and the total cost was about £14,000 to create additional warehousing and a tailoring workshop, as well as stabling for 38 horses, a bakehouse fitted with nine ovens, and a glass-roofed courtyard.

These days, only the High Street frontage survives – the rest was demolished in 1989 – and the façade was incorporated into the Highcross (previously Shires) shopping centre. Peer up to the corner roofline and you’ll spot the 1884 date stone that, who knows, Frederick himself might well have hoisted into position.

1885-6: Clarendon Park Congregational Church, London Road

From Queen Anne style architecture on the High Street, we move to 15th century Gothic on London Road. Frederick Major’s next large project was the construction of Clarendon Park Congregational Church. Built to accommodate 500 worshippers, at a total cost of approximately £7100, the church was designed by James Tait and is located at the junction with Springfield Road.

In its report of the memorial stone laying ceremony in March 1885, the Leicester Chronicle and Leicestershire Mercury described the design thus: “the walling externally is Croft Hill rubble stone with dressings of Derbyshire sandstone and [red] Hollington stone, and the principal external feature will be a bold and massive tower, fronting the London Road, which will extend the whole width of the nave – some 32 feet – and be about 70 feet in height.” The tower is indeed dramatic, topped with corner turrets, but internally the arrangement is simpler, apparently “combining good taste with utility.”

Opened in March 1886, “the church is a very handsome one… it furnishes a fine architectural feature in the locality” and at the celebratory lunch, a vote of thanks was given to the architect and contractor “acknowledging the conscientiousness and ability with which they had carried out their undertaking, and expressing pleasure that not a single accident had happened to any of the men engaged on the building.”

In many ways, Clarendon Park Congregational Church represents the pinnacle of Frederick Major’s building career. He retired in the 1890s and his son Arthur continued the firm until it had to close when Arthur died prematurely in 1906 whilst travelling in South Africa. In contrast, the Duxbury family business continues to operate – these days primarily in upmarket shop-fitting – over 180 years after Thomas Duxbury first started out as a bricklayer and builder.

In later life, Frederick went on to become a member of the Board of Guardians, a Liberal town councillor for the Wycliffe ward – on and off between 1893 and 1924 – and a director of the Leicester Temperance Building Society. There are glimpses of his character in news reports during his political candidacy: “not only well known in the district, but deservedly popular”, “he was eminently fitted for the work of the Town Council by his long experience in the building trade, his well-known uprightness of character, and his reputation as a practical economist”, and “By carrying out the Liberal watchword – Progress, Efficiency and Economy – I trust to merit, with my colleagues, the increased confidence of all the burgesses.”

As we know from his obituary, Frederick didn’t get round to writing a book on life in Victorian Leicester. And, remarkably, I’ve not yet managed to track down a photo of him, though I remain hopeful he’ll pop up in a group photo of councillors one day. Nevertheless, I’m chuffed to have discovered that parts of his legacy still survive – solidly built in brick, stone and mortar – in Leicester Market Place, on the High Street, and in Clarendon Park.

With thanks to the British Newspaper Archive (britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk), Building News, and Clarendon Park Congregational Church.

You might also like to take a look at the other articles in our Trading Stories, Working Lives series:

Jesse Barker, hand-frame knitter and celery grower of Loughborough

Edward Collis, a Victorian cabinet maker, upholsterer and furniture broker

The trial of John Collis, engineer’s patternmaker

George and Anne Waldram, yeoman farmers of Barrow upon Soar

James Powell, an angola spinner of Loughborough

Mary Jane and Clara Bramley, Victorian school mistresses and governesses

Len Collis, a professional musician

John George Collis, a publican in the news

John Collins, a Victorian woolcomber and taxidermist

Naomi Cave, a purse-maker, pub landlady and devoted mother

The Caves of Leicester – Tories or Whigs?

William and Samuel Whittle, yeoman farmers and rabbit warreners of Charnwood

Nathaniel Orringe, miller and baker of Shepshed

Tom Crew, football referee and broadcaster

Samuel Taylor, beadle of Loughborough

Thomas Norman, elastic web weaver

John W Barker & Son, painters and decorators

Mary Ann Norman, Victorian laundress of Paradise Place

John Collins, Victorian fishmonger and game dealer

John and George Firn, monumental masons

Polkey boatmen of Loughborough

The Harrisons: gardeners, nurserymen and seeds merchants

George Robinson, Victorian letter carrier