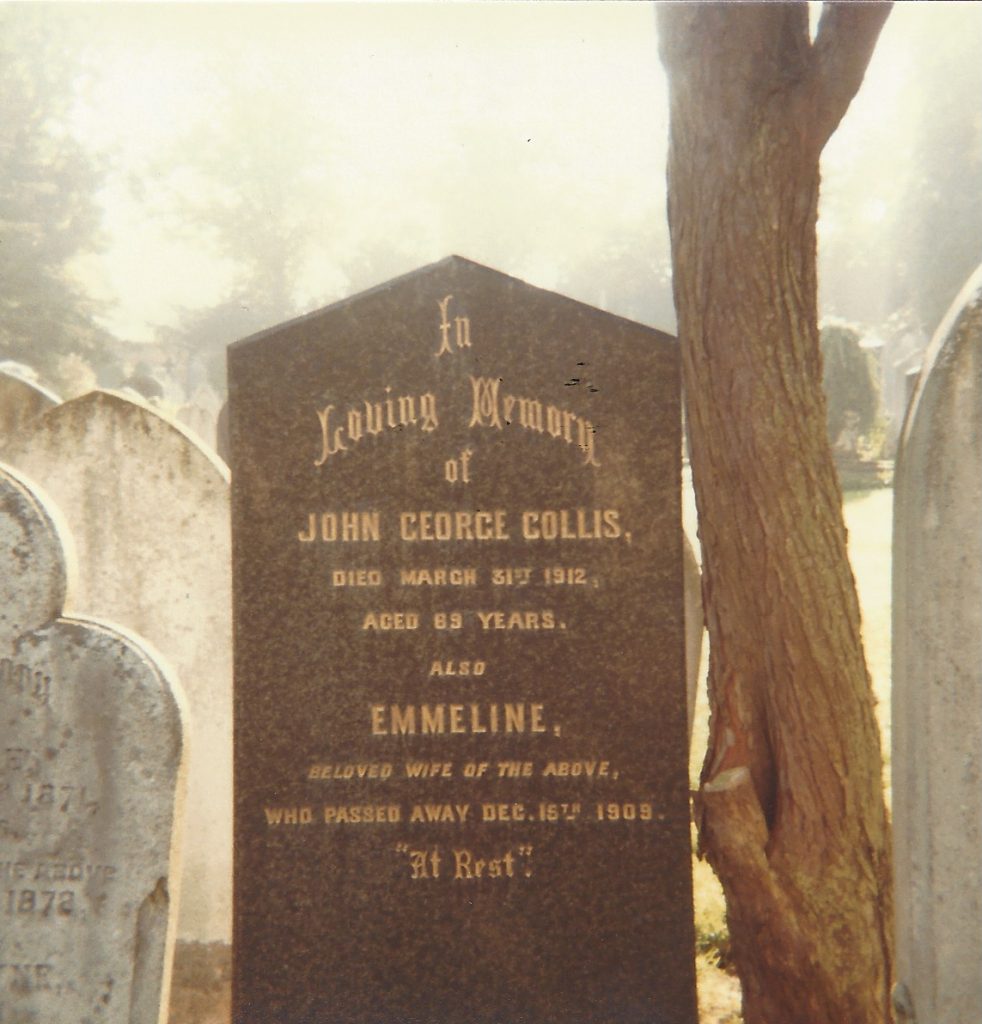

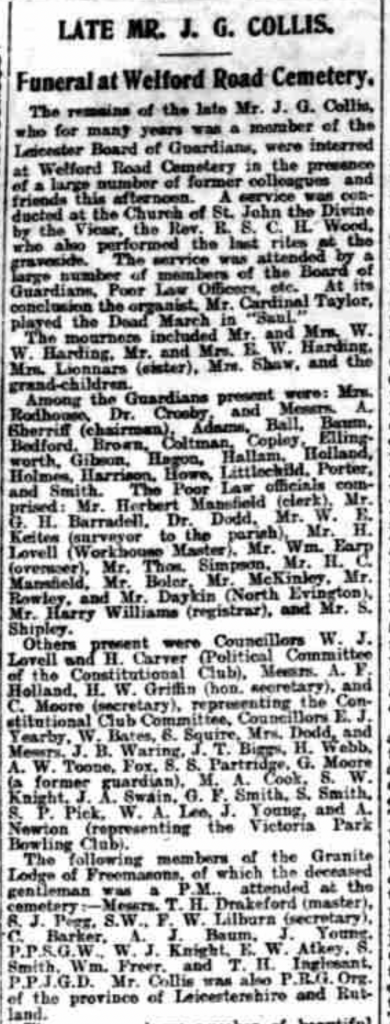

Pause for a moment beside the Symington’s family grave, marked out with a decorative ‘S’ on the stone cross: In Loving Memory of John William Symington. Born 27th December 1856. Died 27th March 1902. Also of Lucy Ada Lionnais. Born 14th April 1862. Died 10th July 1915. Herbert Andrew Symington. Born 8th May 1885. Died 6th December 1928. Margaret Symington. Born 31st January 1893. Died 9th October 1940.

As well as local Leicester voices in their household, I hear Mancunian, a hint of Scottish perhaps, and later French. Let’s hear Aunt Lucy’s back story…

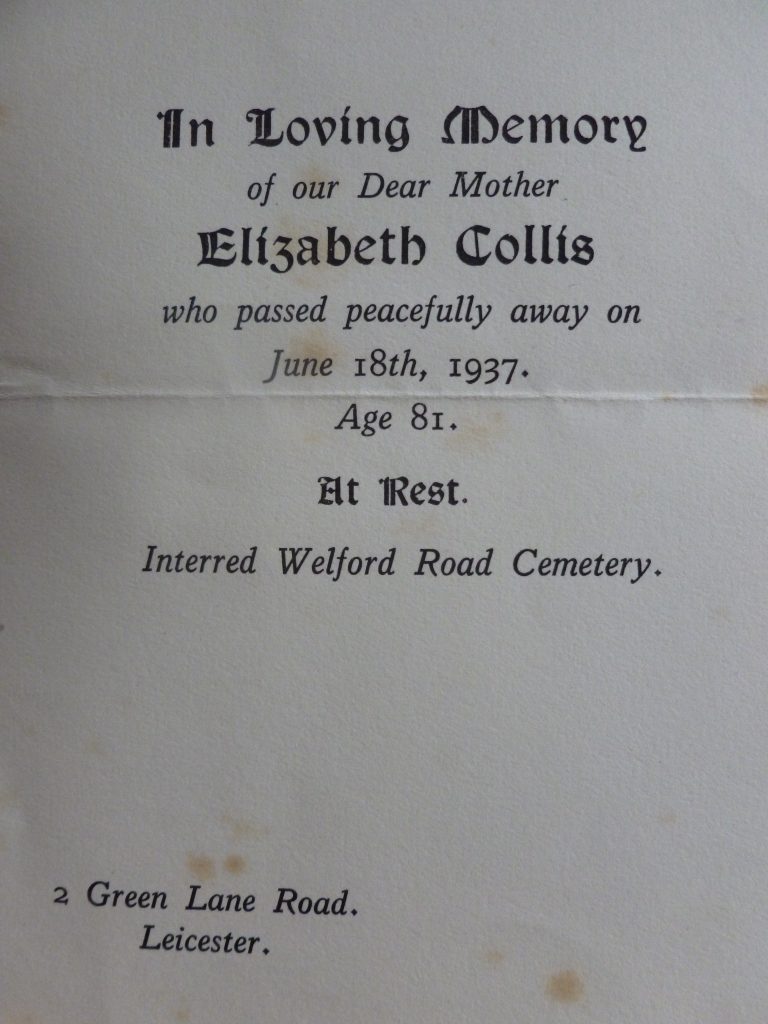

The youngest of eight surviving children of George and Elizabeth Collis, Lucy Ada Collis was brought up living over the family pubs – initially at the Dixie Arms in North Bond Street, and then from the age of around seven at the Spinney Hill Tavern in Upper Kent Street. By the 1881 census, she and two of her four sisters – widowed Sarah Firn and unmarried Matilda Ann Collis – are running the Spinney Hill Tavern, helping their father George (“a retired publican”, he tells the census enumerator).

By the time George Collis makes his will in June 1882, it appears to be only Lucy who is “now residing with me”. He leaves items of furniture to each of his eight children, but Lucy receives “all the residue of my household furniture, linen, china, glass, books, prints, pictures” as well as his Darney pianoforte and £10 (along with Sarah Firn) “for mourning forthwith after my decease”.

The family arranges for the pub, together with three houses George Collis owned at Nos 6, 8 and 10 Gower Street, to be auctioned. “A VALUABLE and well-situated FULL LICENSED House, known as the “SPINNEY HILL HOTEL,”…. now [in the occupation] of Miss Lucy A Collis” is advertised (7 March 1884, Leicester Journal) with details of the accommodation:

Whether Lucy made a winning bid, or instead reached an agreement with her siblings, is not clear. But what is clear is that she was to remain landlady of the Spinney Hill Tavern for the next 16 years or so. It was not a single-handed undertaking but shared with her new husband, John William Symington, who she married in August 1884.

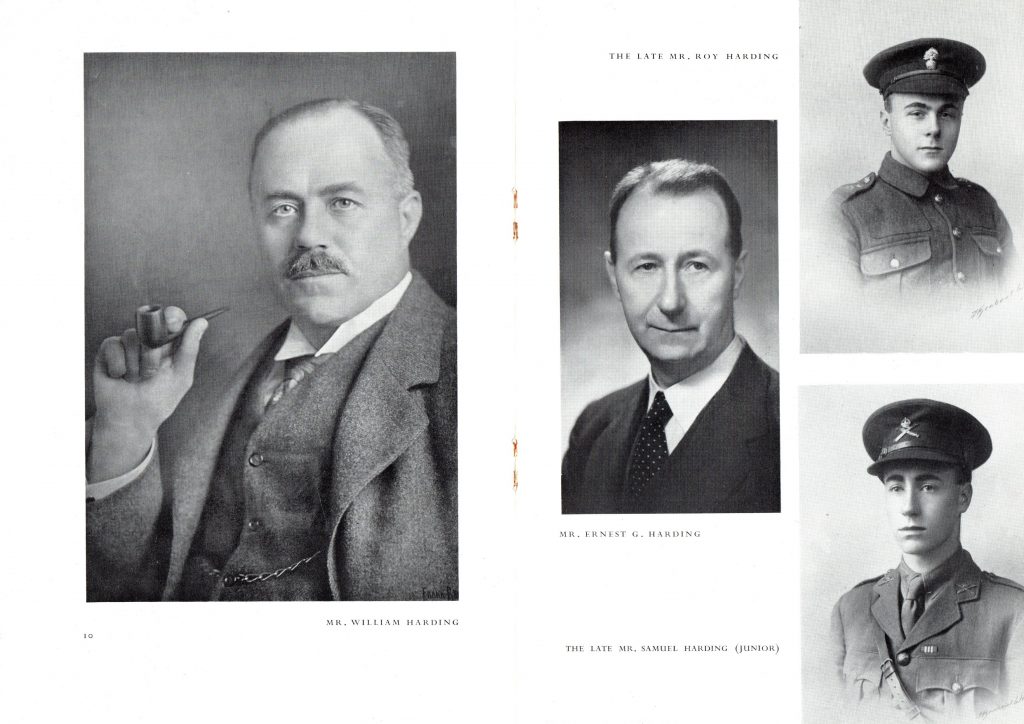

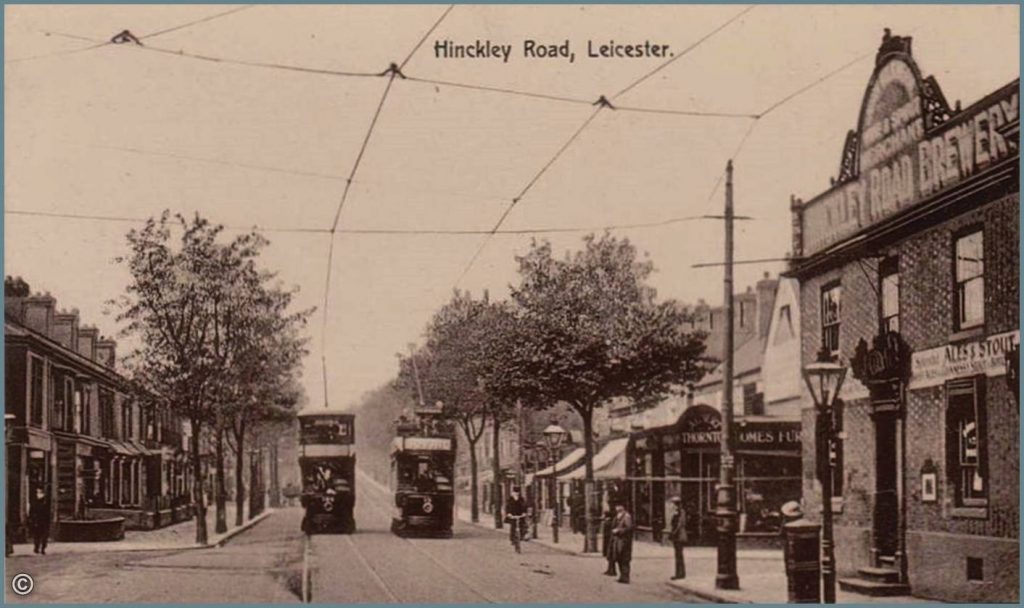

Quite why and when John William Symington – born in Manchester in 1856 – came to settle in Leicester is not clear. He first appears on record in Leicester in the 1881 census, lodging at 20 West Street, but no family links with the town are apparent. Local residents might know of another Symington connection in the county – Scottish-born James Symington (1811-1877) and his wife Sarah established a corset-making business in Market Harborough that became a substantial enterprise – but there are no known links with that Symington family. John William Symington worked as a brewer’s cashier, reflecting his family’s involvement with the drinks trade: his father Andrew Symington had briefly been a publican in Glasgow before becoming a beer store keeper in Hulme, Manchester, his maternal grandfather William Ritchie was a Glasgow wine and spirit merchant (died 1845) and, in turn, his widow Helen Ritchie ran the New French Horn Tavern on Glasgow’s Stockwell Street (1851 census).

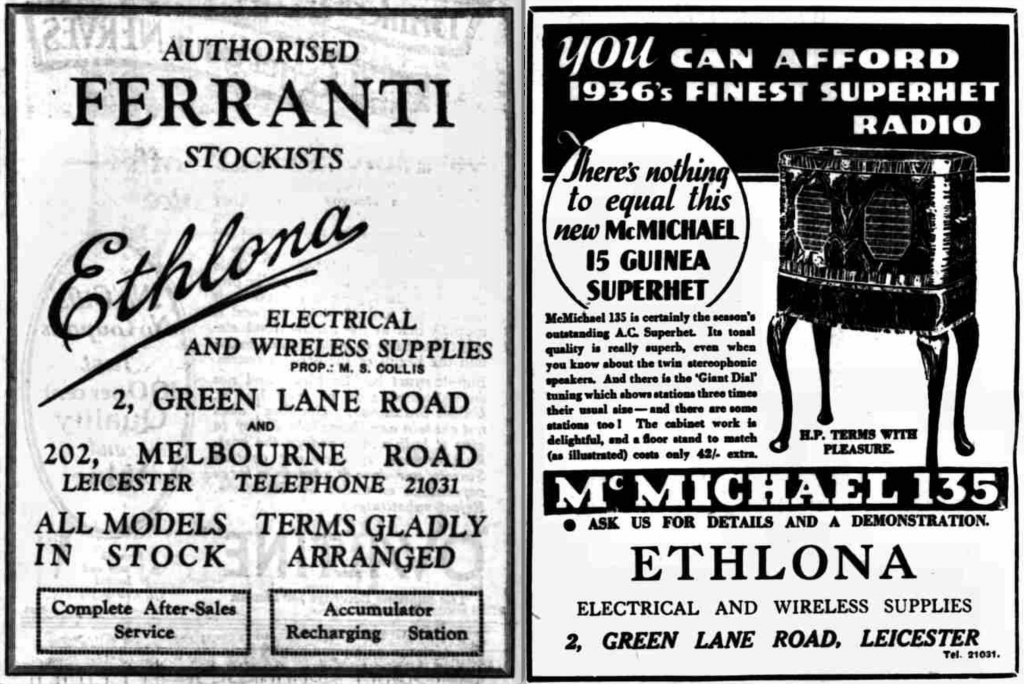

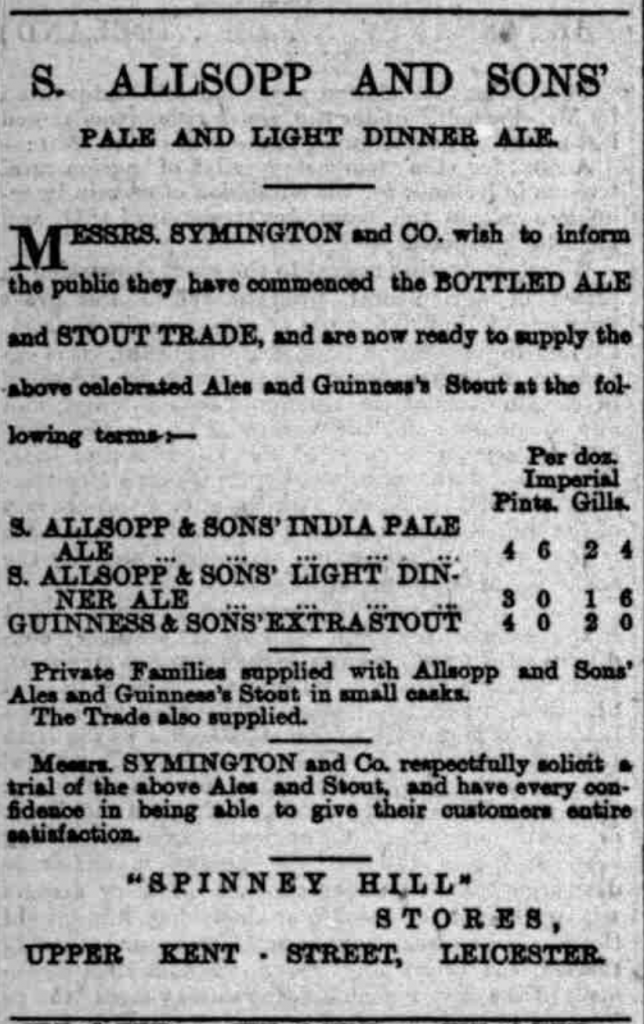

John and Lucy’s son, Herbert Andrew Symington – their only child – was born in 1885. Within a year, they’ve set up a sideline to the pub as “Messrs Symington & Co” at the Spinney Hill Stores advertising their range of bottled beers: Allsopp’s pale and light dinner ales and Guinness stout.

They take on staff – a barmaid, a servant – and business appears to prosper. Links remain close with the Symingtons in north-west England: 5-year old Herbert from Leicester is staying with his Manchester grandparents at the time of the 1891 census, and ten years later the census records John William Symington (by then a 44-year old “retired publican”) staying with his widowed mother Elizabeth and sister Helen (a sweet shop keeper) at their new home in Wallasey. Glasgow accents blend with Mancunian tones.

Having sold the Spinney Hill Tavern around 1899-1900, John, Lucy and son Herbert move to No 18 Lincoln Street, a comfortable house in Highfields. From Melbourne Road School, Herbert wins an exhibition to Wyggeston Boys’ School, where his love of cricket comes to the fore, and he is articled around 1902 to a firm of architects, Messrs Goddard and Catlow, on Market Street. But family life takes a sad turn with John William’s premature death at the age of only 45 years. His probate record adds a further curious detail, as he’s described as “ink and stain manufacturer” as well as previously a “brewer’s cashier and innkeeper” – an enterprising man.

Lucy is on friendly terms with a couple over the road, at 23 Lincoln Street. Francois Lionnais lives with his wife Matilda and niece Leonie Jeanne Lionnais. Born in 1845 in Nancy, east of Paris, Francois had arrived in Leicester in his mid 20s to work as a French master at the Auburn House School in Narborough. As “a resident French gentleman”, Monsieur Lionnais merits a particular mention in newspaper adverts for the school (1873-74).

Maybe the demand for French lessons wasn’t there, perhaps he didn’t enjoy the work, but by 1881 he had shifted career to become a “foreign correspondent” and cashier, working in the Belvoir Street offices of elastic web manufacturers, M Wright & Sons, and lodging at 25 Upper King Street. At the age of 49, he marries Matilda Arkwright of Knighton in 1896 and they settle at 23 Lincoln Street. It’s a relatively short-lived marriage as Matilda dies “after a long illness” in 1905.

Roll forward to 1911; the friendship between over-the-road neighbours Lucy Ann Symington and Francois Lionnais has developed into a marriage. It was a romantic partnership – maybe that French accent worked its magic! – and they enjoyed a comfortable life together at No 23. Lucy is a woman of independent means – she had accumulated a portfolio of 18 rental houses, as well as her home – but Francois continued to work as a cashier, at least in their early years together.

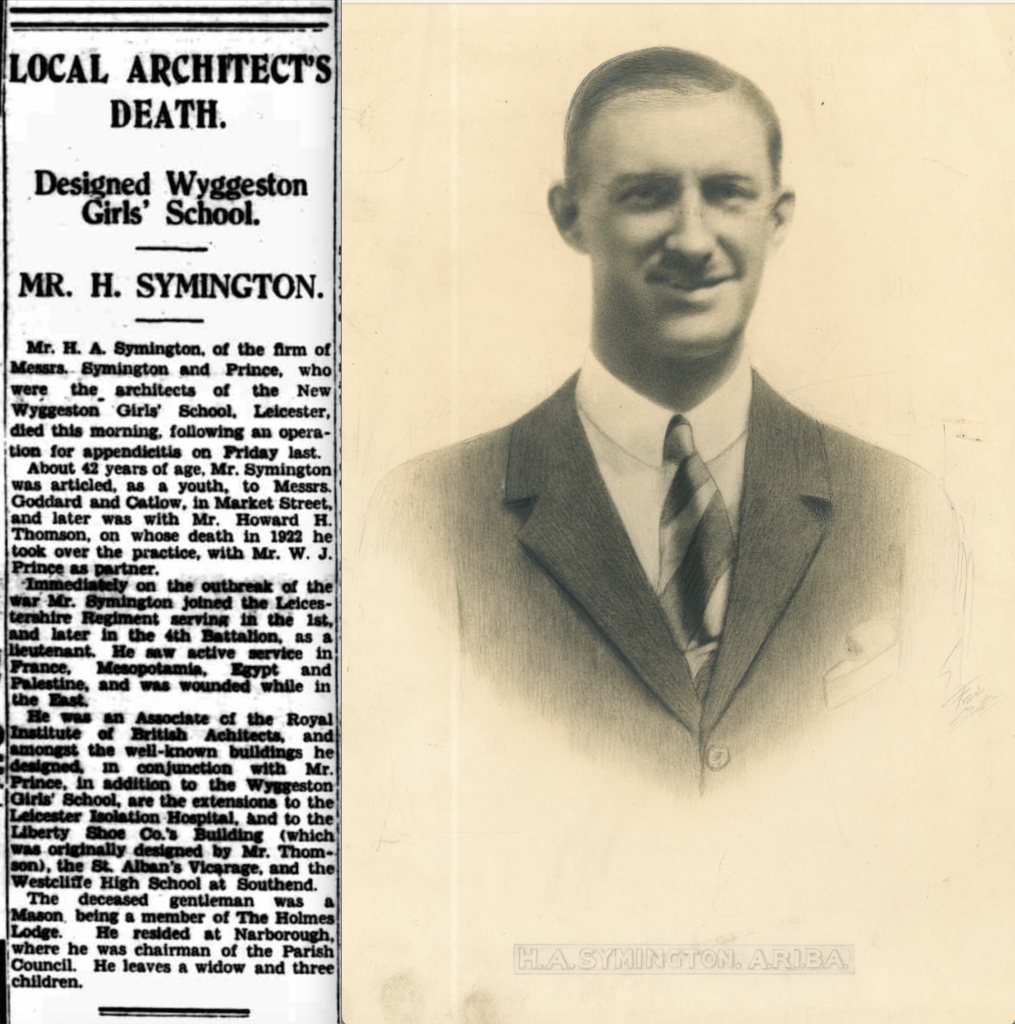

But then WWI intervenes and the family has a tough time. Herbert is called up to join the Leicestershire Regiment in March 1915, “serving in the 1st, and later in the 4th Battalion, as a lieutenant. He saw active service in France, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Palestine, and was wounded while in the east,” as was later recorded in his obituary. His mother, alas, was not to hear of his gallant service as she died in April 1915, a month after he’d joined up. And as the end of WWI approached, Francois Lionnais died in July 1918. The very same month, Herbert married Margaret Wilson – daughter of Narborough boot manufacturer, Fred Wilson – and they settled at Ivyleigh, Narborough.

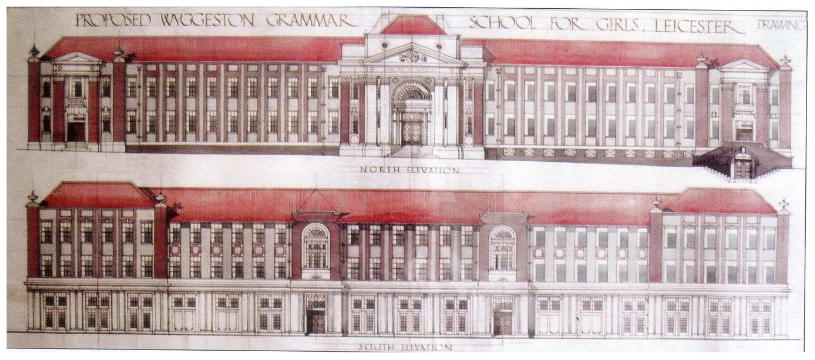

After the War, Herbert resumed his architectural work, initially for Howard H Thomson and then from 1922 in partnership with William J Prince – as Symington & Prince, based at offices in Market Street. His most notable project was the New Wyggeston’s Girls’ School on Regent Road but he also designed the extensions to the Leicester Isolation Hospital, and to the Liberty Shoe Co’s Building (which was originally designed by Howard Thomson), the St Alban’s Vicarage in Leicester, and the Westcliffe High School in Southend.

Rather like both of his parents, sadly, Herbert died at a young age – from complications after appendicitis surgery, aged only 43; who knows what else he might have achieved in a longer career.

When the architectural practice records were deposited at Leicestershire & Rutland Record Office recently, I was delighted to learn that they included a portrait photo of Herbert. And whenever I pass by the Wyggeston Girls’ School (now WQE Wyggeston & Queen Elizabeth College) on Regent Road, I glance across and think of him.

Now, having spent time with the Symingtons, let’s progress to our next family grave at Welford Road Cemetery. You can just about spot where we’re heading by taking another look at the photo at the start of this blog post. In the background, facing the rising lawned area, there’s an angel carved in white marble. From the Symingtons, it’s a very short stroll – head towards the bottom of the stone staircase and then off to the left. It’s time to meet the Pinks….