We’re delighted to share a guest blog post written by Andrew Alston. Here he investigates the life of Edwin Crew – a relative connection he shares with Auntie Mabel founder, Graham Barker. It’s a fascinating account of a remarkable man. Thanks for sharing it with us, Andrew.

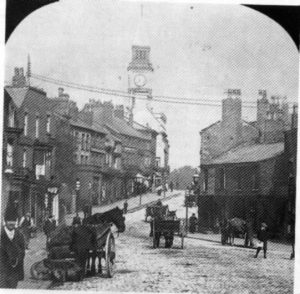

I first came across Edwin Crew while sorting out great great grandmother Alice Preston’s family. Chorley in Lancashire has relatively few families with the Preston surname, despite being only 10 miles from the place where the name mostly originated, but they all seem to have used the same set of common forenames. And so I found Jane Preston, one of my second cousins four times removed, marrying Edwin Crew. I was working at Crewe, so the name stuck out a bit. The newlyweds moved to St. George’s Street, a smart street occupied by people in “the professions”. Virtually all my Chorley relatives worked in mills and mines, so something different was worth following up.

Victoria Chorley: Market Street

Victoria Chorley: Market Street

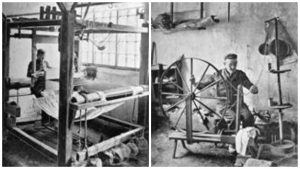

Edwin Crew was born in Spitalfields, in London’s East End, on 8th November 1855. Not the genteel sort of East End shown in the soap opera, but an area crowded with textile workers, mostly weaving silk on hand looms in their own homes, with the “manufacturer” paying them a pittance. Edward Street, where he was born, seems to have disappeared early on. Bacon Street, where the family had been in 1851, consisted of 3 and 4 storey buildings, which by the end of the 19th century had gone even further downhill. Charles Booth’s poverty survey in the 1890s describes “thieves, prostitutes, mess, ragged children”.

Spitalfields had become the centre of silk production when Huguenot weavers fled persecution in France. Later, Jewish and then Asian immigrants would move into the area.

Booth’s poverty map (1889) shows Bacon Street coloured Black: “Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal.”

Edwin’s father, silk dresser Thomas Crew, was born in Spitalfields too – the Crew surname is common there – but had married Ellen Wildgoose 200 miles away in Macclesfield. Macclesfield had become the northern centre of silk production by the beginning of the 19th century, but unlike Spitalfields, work there was organised in a factory system. The Crew name is common in Macclesfield too. A different Edwin Crew owned substantial mills there.

Thomas and Ellen moved back and forth between Macclesfield and Spitalfields. Children were born at each end of their journeys. The places of birth shown in censuses often don’t coincide with the birth registrations, so Thomas and Ellen were as confused as I became. The move sometimes came between a child’s birth and their baptism. It seems likely that the family travelled by train between the places. Thomas appeared to be a silk dyer when in the south, but in the north he was a silk dresser or finisher, applying the right finish to cloth woven by others.

Silk weaving in Middleton

Eventually, the family gave up wandering, spent a few years in Macclesfield, and in 1870 moved a further 20 miles north to Middleton, a smaller centre of hand-loom silk production, but which was in the process of changing over to cotton mills. Thomas was still mostly a silk finisher, but it was now time to get employment for the children. Mary Ann became a sales woman in a boot and shoe shop before marrying in 1872. Herbert stayed in Macclesfield as a silk finisher and eventually took a pub there. Elizabeth was busy with needle and thread before her marriage, back in Macclesfield. Sarah Ellen became a nurse, first in domestic service, and later at the asylum in Lancaster. Emily was also making up silk items before her marriage. Clara went into the cotton mill. Alfred was apprenticed to a saddler.

Edwin, though, apparently didn’t like being a coat cutter. He moved into the printing industry, and to my home town of Chorley. When he married Jane Preston, he was a compositor in Liverpool, presumably at the end of an apprenticeship, but then set up in business for himself in St. George’s Street, Chorley, as a printer and stationer. Victorian society was a great user of printed material. The middle class needed visiting cards, businesses needed receipt books, ledgers registers and handbills. The councils printed electoral rolls. Even the courts used pre-printed forms for everything.

1880: Edwin advertises for a printing apprentice

Business appeared to go well. Edwin started a newspaper, the “Chorley Weasel, a local political and social journal of current events”. The Weasel’s content was mostly local politics, but presented in a humorous fashion. Some of the jokes in there are still doing the rounds. The rest of the paper was made up of fiction serials, international news, scandal, syndicated stories, items lifted from other publications (common practice at the time) and advertising.

In 1882 there was a strike in cotton spinning, because the local employers paid less than those in Bolton. The Weasel printed both sides of the dispute, but took up the cudgels on behalf of the innocents who were coerced by the strikers. Each issue mentions the campaign for Chorley to have its own free library. Edwin campaigned for rights of access to the countryside, and in particular to “The Nab”, a hill to the east of Chorley frequented by generations in their desire for recreation.

Four Crew children were born in Chorley. Three of them would make it to adulthood.

Edwin, as a pillar of the business community, joined the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds, an organisation aimed at helping others. Edwin would rise through the ranks of the Order. “Shepherds’ Hall” is still a major building in Chorley.

Shepherd’s Hall, Chorley

Edwin’s name also appears in the other newspapers published in Chorley, campaigning for the betterment of the population, and even protesting about the proposed closure of the level crossing at Chorley railway station, something British Rail eventually managed a hundred years later.

However, brighter lights must have beckoned. In 1889 – after a brief stay in Buxton – the family moved to Leicester. The census of 1891 has the family is in Biddulph Street, Leicester, an area of better quality terraced houses north of Evington Road. He stayed in the terraces around Evington Road until his retirement. No fancy house in the suburbs for him! Edwin now describes himself as a journalist. He is working for the Midland Free Press, which was published from 1858 to 1917.

It appears to be around this time that Edwin used his position in society to campaign on behalf of the blind, supported by Jane. In 1889 he and Charles Harris formed the Wycliffe Society for Helping the Blind. In 1892, he organised the first “blind holiday”, a day-long visit to Bradgate Park, Leicestershire. In the following years the Society built a hospital, cottage homes and a home of rest in North Evington, having a vision of “a city for the blind” there. Edwin and Jane spent a lot of their time raising money for their cause.

Wycliffe Cottage Homes for the Blind on Gwendoline Road, Leicester

By 1901, another daughter Ethel has joined couple’s surviving children, Tom, Ida and Edwin junior. Edwin is described as a newspaper manager. By 1911 he has become Editor. He was probably editor much earlier, as there are reports of him taking a stance against the Boer War.

All this time he had continued his membership of the Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds. At the 1902 national meeting in Cardiff, he accepted the post of editor of their magazine. The 1903 meeting was to be at Chorley, when he would no doubt catch up with old friends. In 1916 he was elected Chief Shepherd, and used the post to promote the welfare of the blind at the many meetings around the country.

Jane died in 1933, and Edwin retired to Bournemouth, where daughter Ida and her husband were living. He died at the end of October 1939. Edwin junior became a bank manager in St. Anne’s-on-Sea, but continued his father’s work with the blind. In 1939, there are seven blind people staying with him.

Thanks again, Andrew, for sharing your story with us. It has inspired us here at Auntie Mabel to take another look at Edwin Crew and, who knows, write up more of Edwin’s story over the coming months.