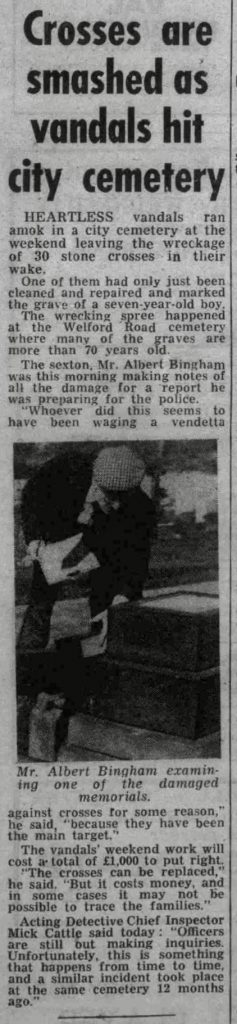

Topped by a large angel, and standing close to the foot of the grand stone staircase, the gravestone of George Pink (1845-1932) and his wife Elizabeth (1851-1922) is easy to find. Sadly, the angel has seen better days; her wings, right arm and left hand have all been broken off. I recall as a youngster, my grandmother being upset as she told us the angel was one of the victims during a spree of mindless vandalism in March 1978. Truncated though she is, and somewhat struggling with grime, the angel always draws me in during my perambulations around the cemetery. A distinctive figure, commemorating my 3 x great Aunt and Uncle Pink.

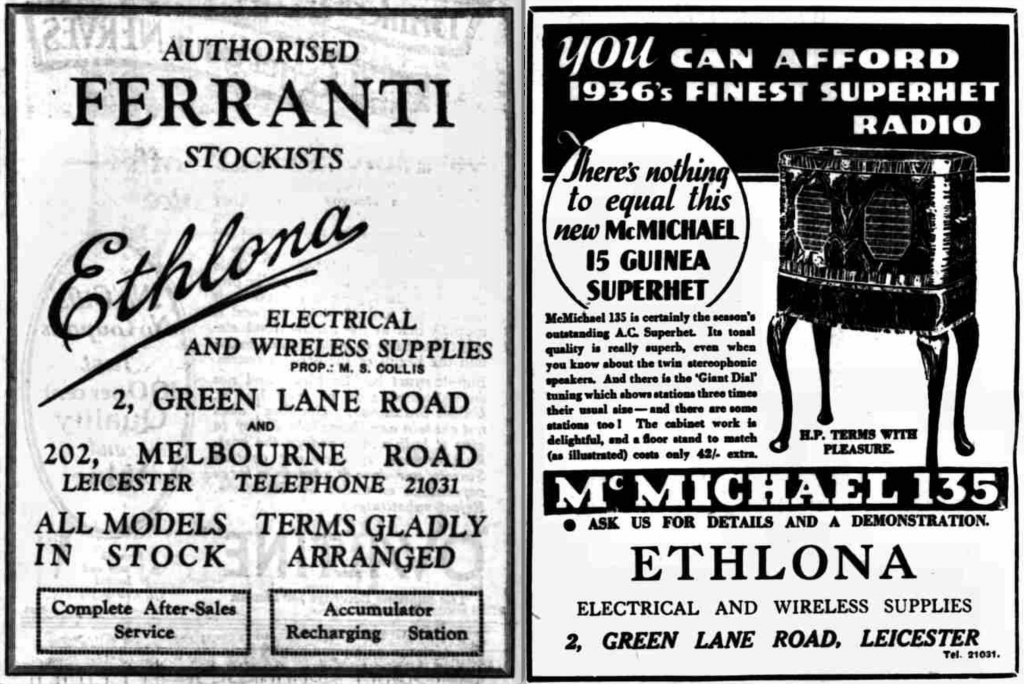

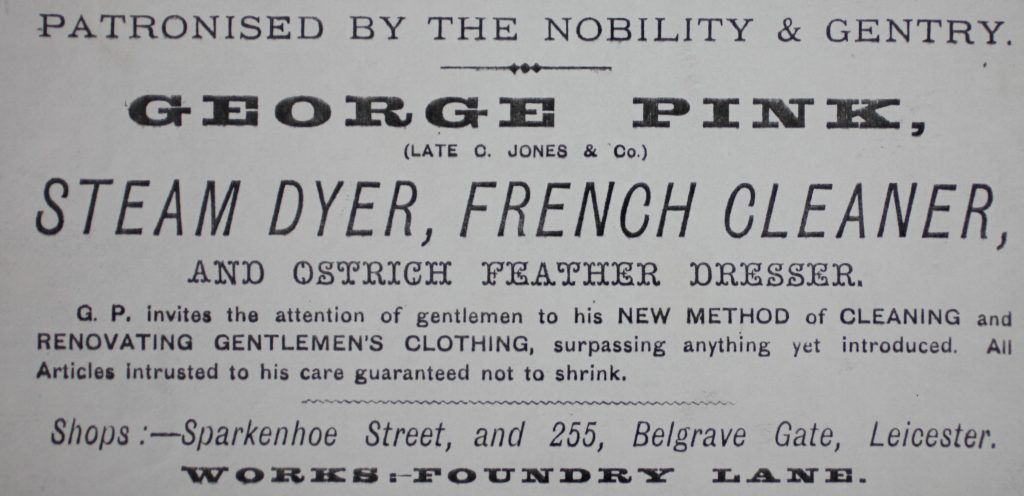

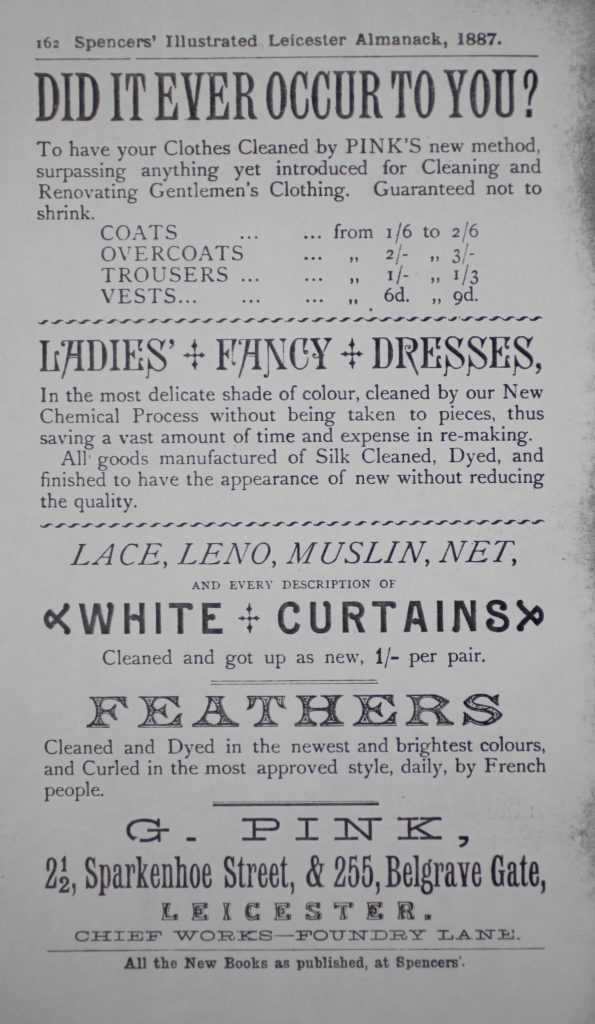

As this advert from an 1880s trade directory indicates, George and Elizabeth Pink set up in business as steam dyers, French cleaners and ostrich feather dressers. Mr Pink seems an apposite name for a dyer, but he wasn’t always in that line of business. Young George, it seems, inherited an entrepreneurial spirit from his father, a railway agent in Peterborough. Orphaned as a teenager, he settled in Leicester and worked variously as a hosier (1869), licensed victualler (1870), warehouseman (1878) and clerk (1881) before joining dyer Charles Jones in partnership.

I unearthed the first mention of George in his new occupation as a dyer in the London Gazette – a surprisingly fruitful online archive, full of bankruptcies and business dealings. It reveals that, on 14th March 1883, the partnership between Charles Jones and George Pink “as Steam Dyers, French Cleaners, and Feather Dressers, under the style of C Jones and Co, has been this day dissolved by mutual consent [and]… George Pink will continue the said business on his own account.”

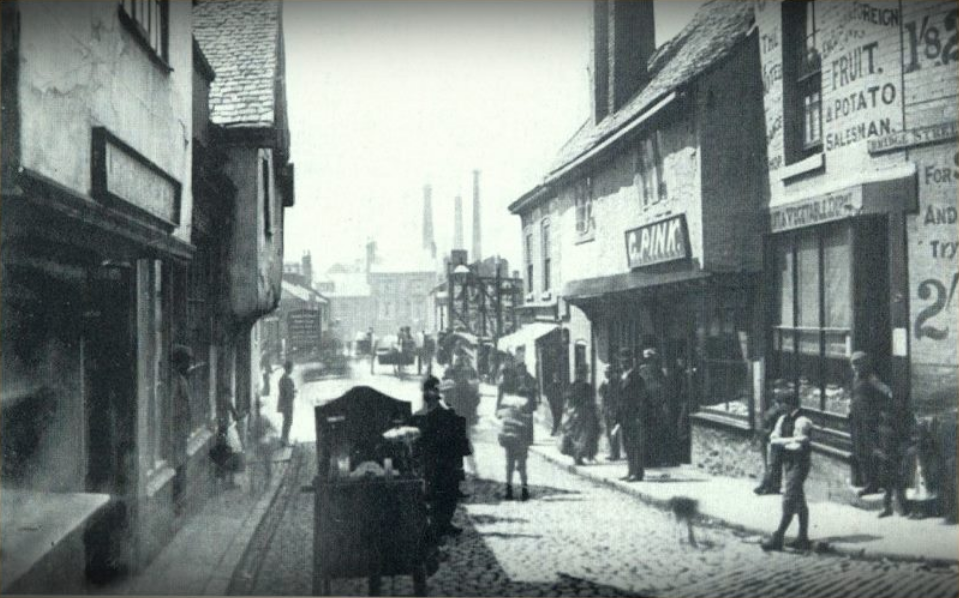

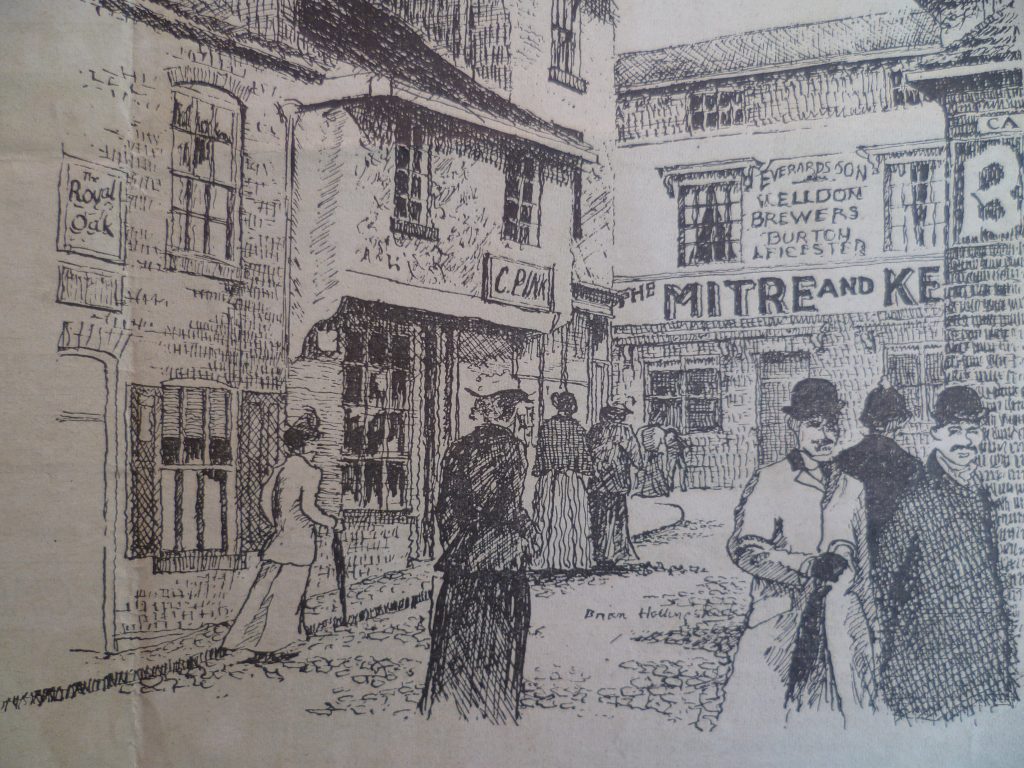

George’s decision to take on Jones’ dyeing business was a well-judged move. Leicester trade directories during the ensuing two decades witness his expansion from two to seven shops, dotted throughout the town. A few grainy photos of one of the shops survives – in the almost Dickensian streetscape of West Bridge Street – and it was later sketched for a Leicester calendar in the 1980s. Here, and at their other shops, George’s wife Elizabeth and her team would welcome and serve their customers.

Pink’s ‘chief works’ were initially at Foundry Lane. Old Ordnance Survey maps come in handy to capture a sense of the streetscape; trace around Foundry Lane and you can almost smell the pungent whiffs arising from the cement works, bone factory and gas holders clustered around the Leicester Canal.

By 1889 George had relocated his works to Guthlaxton Street in Highfields, an altogether more residential part of town. His house and works there are long since demolished but counting, plot by plot, on an old map gives me the lie of the land. From his home at 54 Sparkenhoe Street he could nip through the back gate onto an alleyway, which in turn led to the dye-works, nestling squarely behind red-brick terraces.

Inside, the dye-house would have been equipped with large steaming coppers and iron pans. Ladies’ dresses would be steeped in dyestuffs, coloured according to fashion and fancy. Wringing posts, mangles, drying rails and steam irons are on hand for finishing off.

Traditionally dyeing had been a drawn-out process, with some batches taking weeks to turn out. In the early nineteenth century, it could involve soaking fabric in successive baths of lye, olive oil, alum and dung, to help the indigo or madder dye take hold.

But dyeing technology was revolutionised in 1856 when William Henry Perkin discovered, by accident, the first aniline dye. Whilst cleaning his chemical flasks after attempting to synthesise quinine, Perkin noticed that the rich purple residue – later christened mauveine or ‘mauve’ – acted as a colourfast dye. His discovery kick-started the synthetic dye industry; dyestuffs that had previously been extracted slowly and unpredictably from plants, roots, insects and shellfish could now be produced on an industrial scale from coal tar.

Perkin made his fortune and dyers such as George Pink were able to offer their customers a spectrum of colours. With only sepia photos available, it’s easy to forget that Victorian women’s dresses could be colourful. And men’s attire might be vibrant too, as journalist George Sala observed in 1859, “If the morning be fine, the pavement of the Strand and Fleet Street looks quite radiant with the spruce clerks walking down to their offices… the pea-green, the orange, and the rose-pink gloves; the crimson braces…”

But perhaps most significant to Pink’s was the Victorian preoccupation with mourning dress. There was a complex protocol of mourning attire, especially for women. New widows would dress for thirteen months – a period known as ‘First Mourning’ – in black bombazine, covered with crepe, a widow’s cap and lawn cuffs. The crepe and bombazine layers were reduced – and jet jewellery and ribbons added – through ‘Second Mourning’ and ‘Ordinary Mourning’. And finally during ‘Half Mourning’ – oh what relief – greys, lavenders and mauves could be introduced. All in all, the dyeing and cleaning of ‘widow’s weeds’ – coupled with the more industrial dyeing needs of a hosiery town like Leicester – could be big business.

As well as dyeing, Pink’s offered ‘French cleaning’ – or dry cleaning, as we know it today. His ‘New Chemical Process’ was guaranteed not to shrink clothing and could get up net curtains ‘as new’ for a shilling a pair. Rather like Perkin’s discovery of synthetic dyes, French cleaning came about by accident; in 1855, a French dye-works owner Jean Baptiste Jolly noticed that his tablecloth became cleaner after his maid accidentally overturned a kerosene lamp on it. Jolly began to offer ‘dry cleaning’ to his customers and its popularity took hold.

By the 1890s – with new shops on the High Street and Humberstone Road – George Pink was prospering. As the Leicester Chronicle and Mercury noted in their 1893 feature on ‘Christmas Preparations in the Shops’:

“The art of dyeing dress and other materials has of late years advanced at a great rate, with the result that some really beautiful work is now turned out. Mr G Pink of Sparkenhoe-street and 255 Belgrave-gate is rapidly taking a leading position in this branch of business, the dyeing of feathers and dress material being a special feature with him.”

So, at Pink’s you could also have your ‘Feathers Cleaned and Dyed in the newest and brightest colours, and Curled in the most approved style, daily, by French people.’ Dress historian and photo detective Jayne Shrimpton writes about the fashion for ostrich feathers:

“Neat hats of the 1860s were often trimmed with the tip of an ostrich feather or a bird’s wing, or were circled with feathers,” she explains. “Fashions grew more elaborate and by the late nineteenth century it’s unusual to see a woman’s hat that doesn’t include an arrangement of bows, flowers and plumage.”

But feathers were not restricted to hats. “They might also be incorporated into earrings and corsage ornaments,” Jayne continues, “and fans also became ultra-fashionable during the 1870s and 1880s, trimmed with a natural or dyed feather edging.”

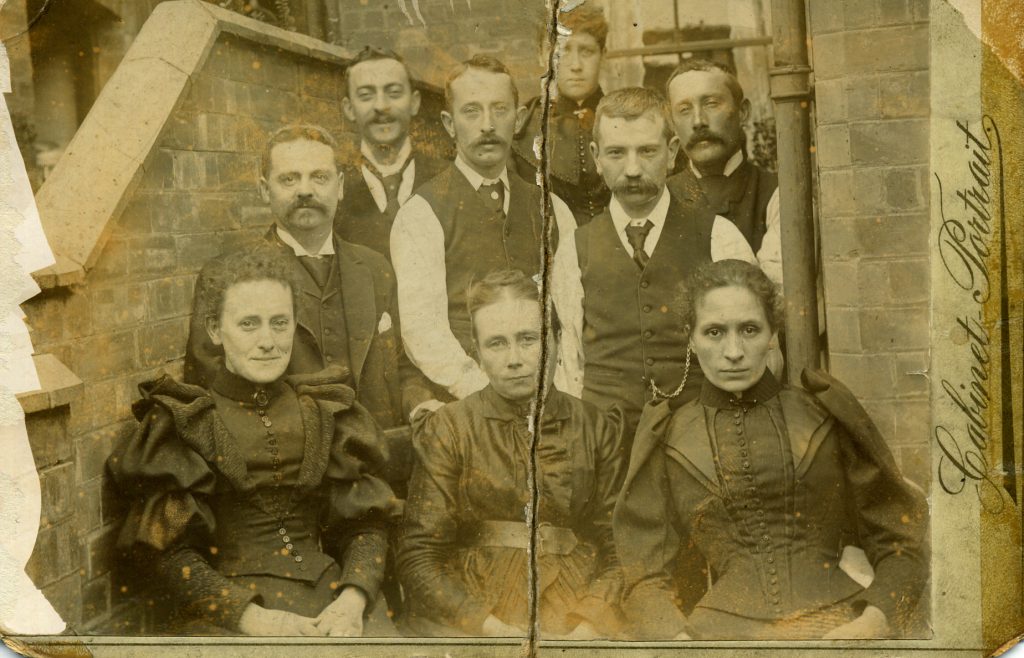

Pink’s French feather curlers would have been kept busy, and family tradition too has it that Elizabeth Pink, George’s wife, was a most accomplished feather dresser. Alas, she isn’t sporting any feathers in her studio portrait, though she and her husband George still look rather spick and span.

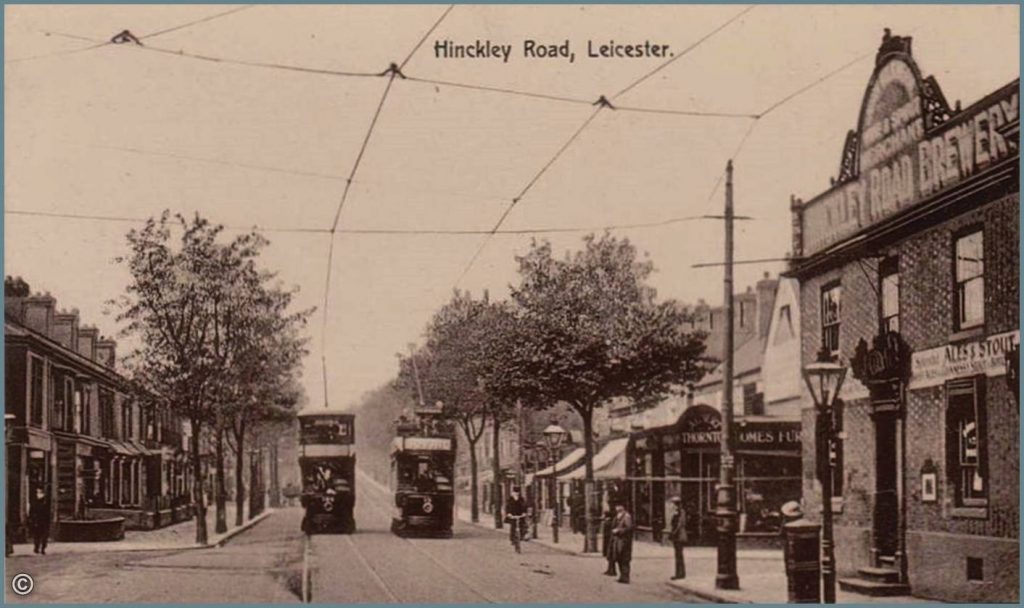

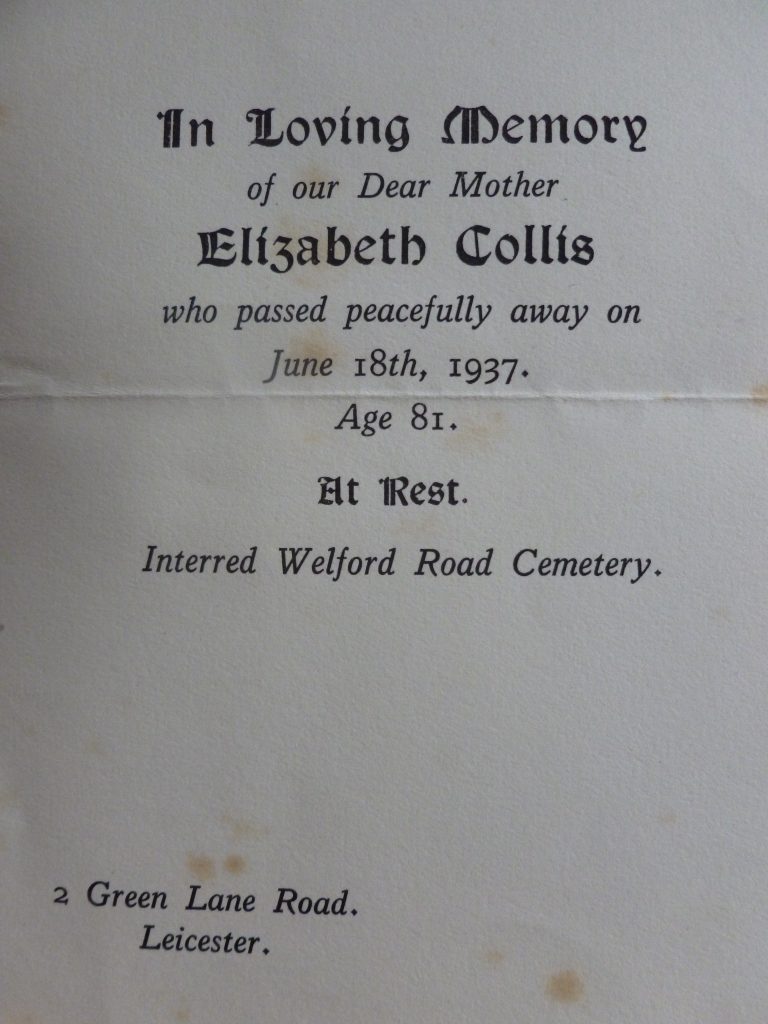

By the 1901 census, the Pinks have retired from business. They later move to a substantial villa – Carnation House – appositely named, facing Victoria Park. They are generous hosts to an extended family of nephews and nieces. My Grandma and Auntie Mabel spoke fondly of visits to Uncle and Aunt Pink. And for my part, I visit their grave at Welford Road Cemetery from time to time.

Over a century later, the only tangible remains of Pink’s business are a few adverts, photos, newspaper snippets and inherited family memories. Yet with a healthy dose of imagination I can envisage their Victorian dye-house in Highfields, steaming with vats of bombazine black, with a flurry of French folk curling ostrich feathers in their workrooms alongside.

For the next family gravestone in my Grave Encounters series, we leave the Flat, head up the stone staircase and – after skirting round the right-hand side of the modern-day commemorative plaques, installed on the footprint of the old chapels – head to the perimeter pathway. Turn right and a short way along on your right-hand side, look out for William and Harriot Barker…